Hands up if you’ve ever skimmed a stone.

Chances are you’ve had a go at some point, maybe when you were a kid or holidaying on the coast. What feelings do such memories stir in you? A sense of fun perhaps, of a challenge, or an impression of being in the moment?

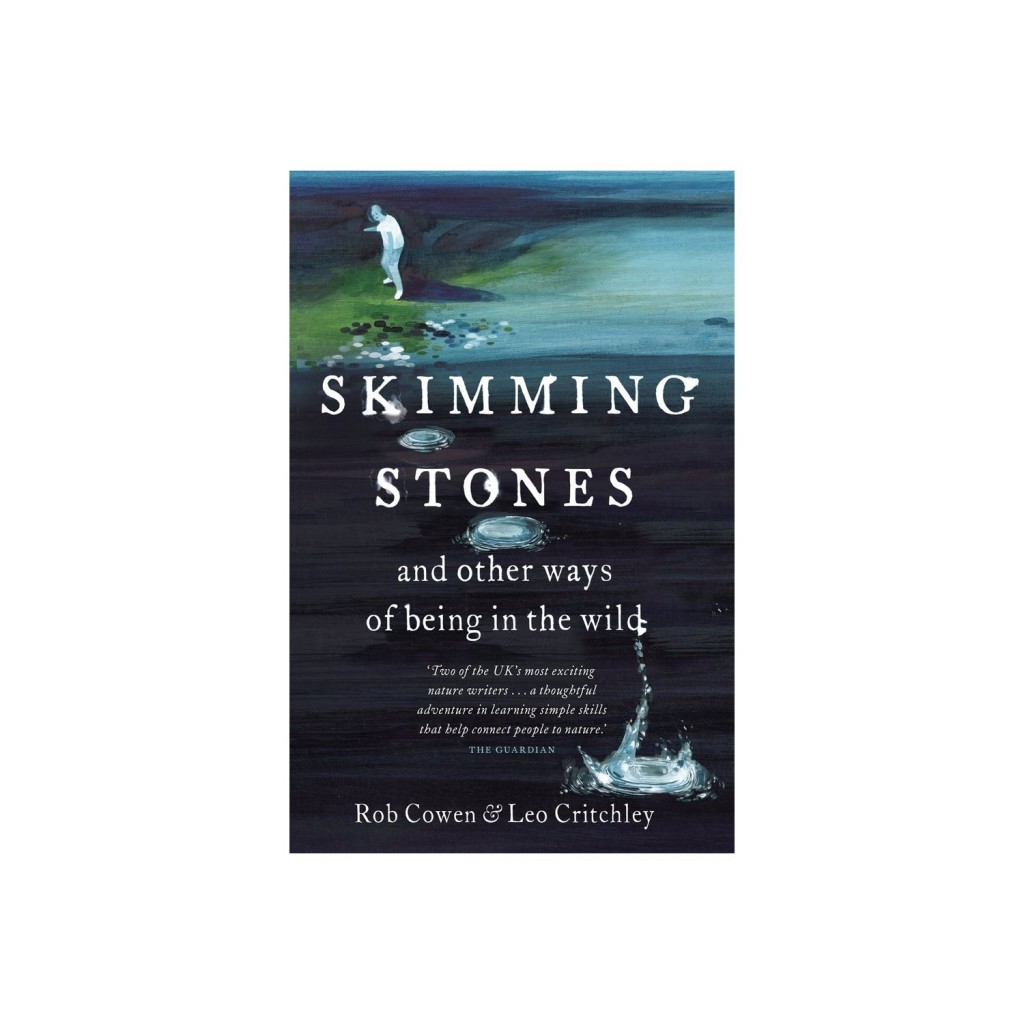

Skimming stones is a simple activity, it may even seem childish, but in keeping with the other activities in our book Skimming Stones and other ways of being in the wild, we believe it is deeply valuable.

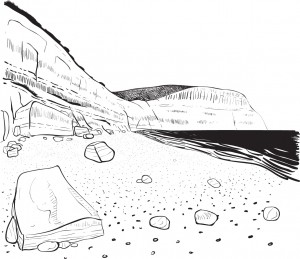

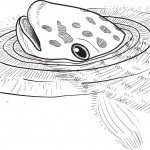

That moment, skimming a stone over the waves, can lift us out of the ordinary rhythms and demands of day-to-day existence. When skimming stones, we enter a different way of being in landscape – we slow down and look more closely at the things around us. Scrabbling in the sand and rockpools in search of the perfect stone, the salt tang heavy in our noses, passing time in the alien terrain of the seashore, we can’t fail to interact with the landscape more deeply.

And it’s not just skimming stones. Do you remember building dens, making dams, and sleeping out by a fire? These are skills previous generations knew but that are disappearing from our society.

For many of us, growing up and trying to carve a place in the world means submitting to the demands of modern life, letting the daily grind dictate our every move. As urbanites we forget the riches that lie around us, drawing the curtains against the call of the owl and cry of the fox, spending our rare breaks in jet-fuelled escapes or at carbon-copy resorts. At home our experience of nature is filtered through laptop screens and HD TVs, our meals are shrink-wrapped and from around the globe, our daily movements via the climate controlled cages of cars, buses and trains. If we do spend time in the outdoors, we march through it from A to B; we ‘do’ a walk or ‘climb’ a mountain, projecting goals onto the landscape rather than taking the time to really be in it.

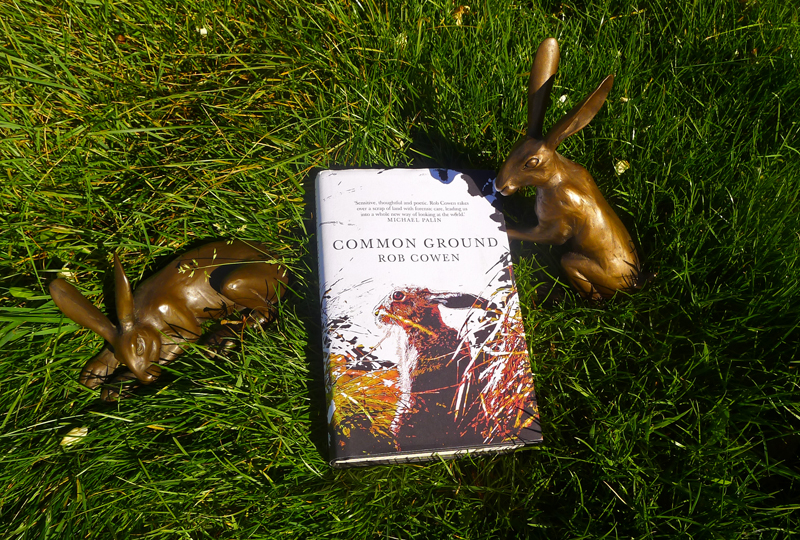

It is this unhealthy state of dislocation that Rob Cowen and I set out to redress in our book. As cell-mates imprisoned in the concrete and glass of a central London office, we found we shared a yearning for the open spaces of our childhoods and struck on an idea for a book of simple activities that would help all of us draw closer to the landscapes we evolved to exist in.

When Rob and I first went looking for reconnection, we started out setting challenges for ourselves and trying to push to the extreme, or at least our extreme. We wanted to conquer mountains, but in the end it was the simple things which gave us what we were looking for. From tracking animals through a forest to making kites out of bin bags and bamboo, our book shares techniques that help ease us out of our day-to-day lives. At the same time we explore the scientific and philosophical reasons why time spent doing these things in the outdoors so enriches our bodies and minds. It invites the reader to look more closely at natural world and, in so doing, their own nature.

Our journey showed us that by taking some time to reconnect with nature, you can throw off a layer of exterior concerns, relax, enjoy who you are and the world around you, and gain a more philosophical outlook on life.

There’s a tendency for self help and personal development books to put themselves forward as the one true route to happiness. That can be hubris, certainly, but it’s often part of the efficacy: the placebo effect is very real, but the placebo effect doesn’t function unless you believe it.

Will reading Skimming Stones change your life? Of course it will, but how much so is up to you. Connecting with nature has the advantage over more esoteric approaches that it is something with a growing body of research and evidence behind it, and a reasonable claim to having millions of years of evolution in its favour. That said, it’s all about what works for you.

Ultimately, whether you see a route to inner peace in it or not, skimming a stone is great fun too, so why not give it a go? Skim a stone! Buy the book! Take the time to support the foundations of your character.

– Leo –

Postscript:

We wrote this book so you can open it on any page and find something to take away.

- The ‘How To’ for each activity is explained so you can try it yourself.

- It is supported by our reflections on why and how doing these activities has such a profound and important effect on us.

- Each chapter is also a narrative of our own experiences, which can be enjoyed from an armchair without needing to recreate them.

- More adventurous readers may want to use the instructional elements as a basis for day trips and long weekends and all the facts and techniques are provided to enrich a personal experience.

- We also dig up of the ‘lore’ of the land – historical and cultural odds and ends, as well as topics as broad as geology, myths and legends.

Our hope is that you will ultimately discover a new side to yourself and be driven to uncover your own ways of being in the wild.

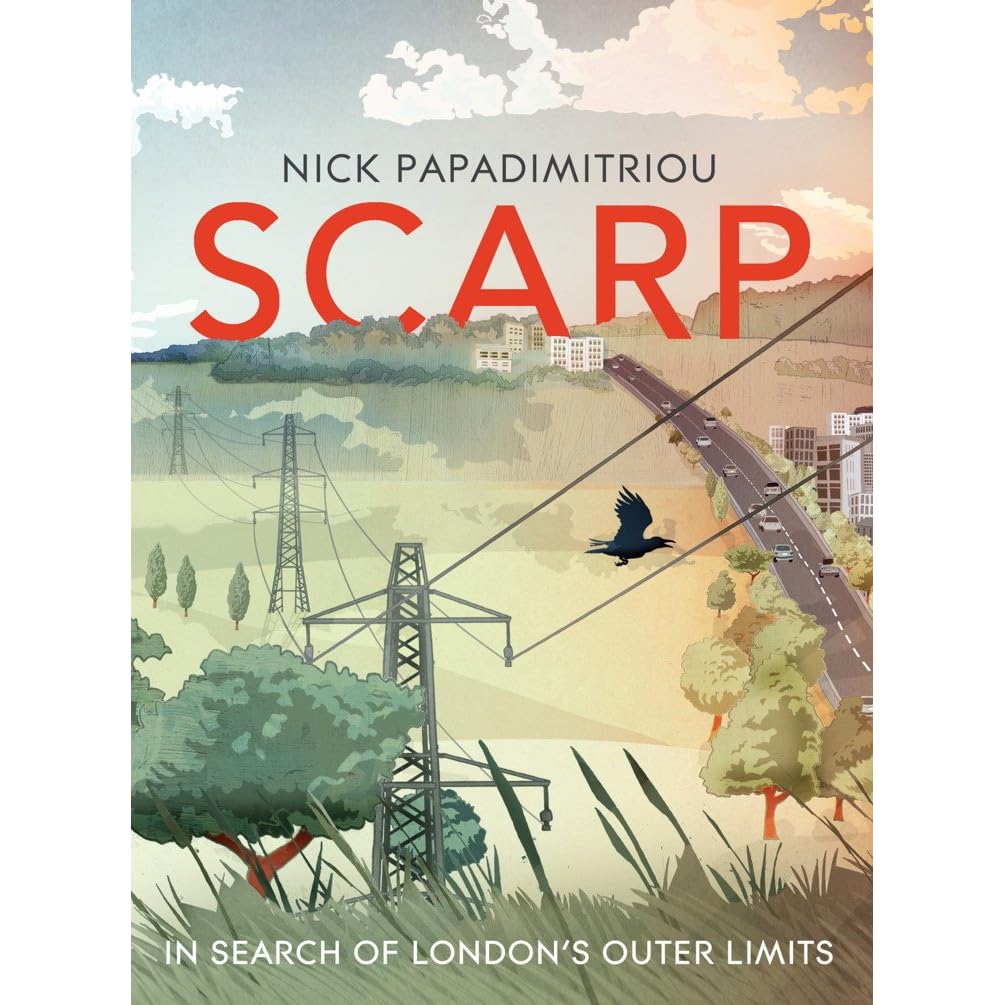

To say he walks the road less travelled is somewhat of an understatement. His latest book Scarp traces a path over the fourteen-mile ridge of land on the fringes of Northern London, through time, in and out of consciousness and between fantasy and truths that are stranger than fiction.

To say he walks the road less travelled is somewhat of an understatement. His latest book Scarp traces a path over the fourteen-mile ridge of land on the fringes of Northern London, through time, in and out of consciousness and between fantasy and truths that are stranger than fiction.